Happening Now

Chicago to Los Angeles: two-thirds of a continent, 528 city-pairs, and one train

September 17, 2012

Written By Sean Jeans Gail

This week, NARP released a white paper looking at the unique benefits of long distance trains. As part of that, the NARP blog will be publishing excerpts from "Long Distance Trains: Multipurpose Mobility Machines" to highlight key findings and recommendations.

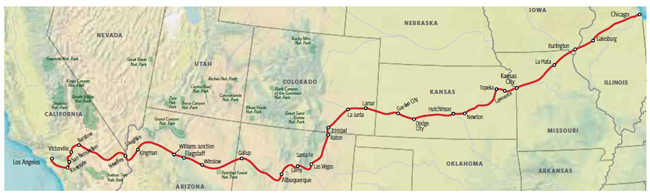

The first entry uses the route of Amtrak’s Southwest Chief to illustrate the unique benefits of long distance trains, and dispel misconceptions about how passengers use long distance trains:

[C]onsider the 2,265 mile corridor between Chicago and Los Angeles. Critics claim that air travel has made such routes obsolete; that it would be cheaper for government to buy each passenger an airline ticket than to run trains on this route. If trains ran non-stop between these two cities, the critics might be right. But the trains do not and the critics are wrong.

This route currently has just one train a day in each direction, the Southwest Chief, yet it attracts 355,000 passengers per year—466 per departure. Because it makes 31 intermediate stops, it provides a mobility choice for twenty five million Americans who live within just 25 miles of a station (31 million who live within 50 miles) for short, medium and long distance trips between 528 different city pairs with each and every trip.

Data demonstrate that trip lengths vary from very short (as few as 10 to 40 miles) to very long (more than 2,000 miles) and everything in between. Please note that many passengers connect to other trains at Chicago, Kansas City and Los Angeles, so many trips are actually longer.

The large metropolitan areas at each end point generate nearly three fourths of all traffic, but:

· Only 8% travel the entire distance between Chicago and Los Angeles;

· 64% travel between the one end point city and intermediate points;

· 28% travel between intermediate cities;

· 19% travel between city pairs where the passenger volume is less than one trip per day: markets so small that only trains with the multiple intermediate stops could economically serve.

Long distance routes not only make transportation sense because they serve so many more markets every single trip than air ever could, they also make financial sense. The economic benefits of attracting people who travel long distances is substantial. Consider that the people who travel the entire distance between Chicago and Los Angeles account for just 8% of passengers but 20% of the route’s total revenue. Consider further that:

· People who choose budget priced coach seats for trips shorter than 750 miles (the definition of a corridor route under federal law) account for 54% of passengers using this route but less than 37% of its revenue. By contrast, people making trips longer than 750 miles, even though a minority of travelers, account for 63% of revenue needed to defray operating costs.

· Put another way, by providing comfort suitable for overnight travel and the convenience of a single seat ride, the route attracts 87% more people and generates 172% more coach revenue than short distance passengers alone.

· The addition of sleeping car service further bolsters revenue. The people who choose this premium priced service account for just 17% of passengers but 44% of total revenue, adding 78% more revenue than coach service alone.

· Sleeping car service generates such a disproportionate share of revenue because the average fare per mile is double that in coach and the average trip is 82% longer.

· The average trip in sleeper is longer because few people make short distance trips in sleepers, not because people do not make long trips in coach. They do. In fact, even for trips longer than 2,000 miles, 27% more people choose coach than sleeper. (97% of passengers making trips under 500 miles choose coach)

All of the other long distance routes in America’s train network exhibit similar usage patterns (except Auto Train, which makes no intermediate station stops).

Long distance trains are cost efficient—a finding that may surprise many. Despite years of neglect and underinvestment, Amtrak’s national network is able to move one passenger one mile (the accepted industry measure of efficiency) at an average public cost roughly equal to shorter corridors outside the Northeast Corridor. This parity is hidden in Amtrak’s financial reports because they include state—but not federal—payments for service as revenue.

Since a substantial portion of the costs assigned to the various routes are fixed, there is an opportunity to lower units costs by adding more service. Congress could further improve efficiency and reduce cost by funding the replacement of Amtrak’s relatively old long distance fleet with modern, high performance trains.

In summary, increasing and expanding service on long distance routes represent an effective and economically efficient method for providing the American people with attractive and affordable mobility choices for many different types of trips to a wide variety of destinations.

The key to this is that one train can mean different things to different communities. Long distance routes represent connected and overlapping corridors that serve multiple regions—and feeder networks, for a variety of transportation modes. For some passengers, it’s a convenient alternative to another mode. For others, it’s a vital economic lifeline.

"Thank you to Jim Mathews and the Rail Passengers Association for presenting me with this prestigious award. I am always looking at ways to work with the railroads and rail advocates to improve the passenger experience."

Congressman Dan Lipinski (IL-3)

February 14, 2020, on receiving the Association's Golden Spike Award

Comments