Happening Now

A Pop-Up Transit System for a Pop-Up City

September 11, 2025

by Jim Mathews / President & CEO

Today, I’d like to use an aviation story to tell a transit story.

Every summer, the sleepy city of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, becomes quite literally the single busiest airport in the world. A little more than a month ago, more than 700,000 people – nearly 11 times the population of the city – converged on Wittman Regional Airport for the Experimental Aircraft Association’s AirVenture fly-in and air show.

For a week, the airfield becomes a pop-up city, a small metropolis, with tens of thousands of people camping, showering, eating, and moving around the 2.3 square miles of the show grounds. I know, because I’m one of about 6,000 volunteers who help every year to put it together and keep it running.

Volunteers do everything from organizing First Aid to cleaning up the grounds, organizing aircraft parking, and even cool jobs like mine – I work in the control tower for the Warbirds area of the show.

Here's the transit part. Another thing volunteers do is operate a regular tram system. Five regular routes together move an astonishing 70,000 riders every single day, with roughly five- to seven-minute headways. And here’s the kicker: those trams are free. For one week each year, the tram system at AirVenture moves more people than the entire transit networks of small and mid-sized American cities. Without charging fares.

It’s easy to dismiss “free transit” as a nice-to-have perk, but in Oshkosh it’s much more than that. The trams are the circulatory system of the entire event. They carry visitors to food vendors, souvenir stands, aircraft displays, forums, workshops, movies, and concerts.

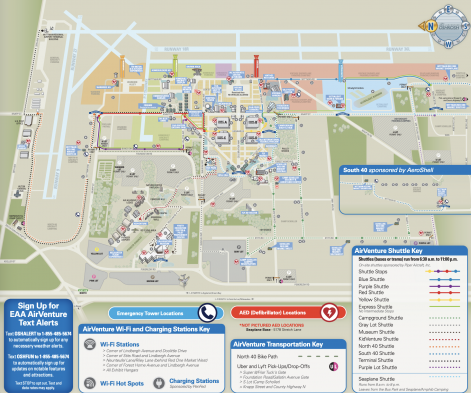

The Red and Yellow lines each run roughly north-south and come together at the show center from the northern end of the show grounds, a spot known as the “North 40.” The Yellow line is the shortest run, but it relieves a lot of congestion at the show center, where four exhibition buildings become very crowded with foot traffic.

The Yellow line connects passengers from the north heading south to catch either the Blue line – a run of more than a mile and a half from close to the show center to the South 40 – or the Green Express line, a no-stops tram between the makeshift “Transit Center” where the Yellow, Blue, and Green all connect, and the South 40. The Purple line runs a shorter but very heavily used loop around the Warbirds parking area, where nearly 400 World War II-era aircraft wait their turn to take to the skies every afternoon.

Show-goers camped in the North 40 use those trams to buy groceries at the Red One Market just west of the show center. Day visitors hop the trams at the Admissions Gate to head south toward food venues along Wittman Road or to buy hats (and sunscreen!) at the Vintage Red Barn. And so on.

By my estimate, those 70,000 daily tram riders generate about $8.2 million in spending on the show grounds alone during that single week — part of the broader $250 million economic impact the event has on the Oshkosh region. That’s not a cost; that’s an investment that pays off. Zero-fare service removes barriers and friction; no one hesitates to hop on to explore, eat, shop, or attend events.

And with 70,000 daily trips across six tram routes, the AirVenture tram system rivals or surpasses many small U.S. transit systems. EAA is famous for running the busiest airport in the world during AirVenture. But its tram network, though temporary, also holds its own against everyday U.S. transit systems. Syracuse, N.Y.’s Centro bus system carries about 42,000 passengers each day, serving a metro area of about 660,000. Toledo, OH, has the TARTA system, but it carries only 6,200 passengers each day around a metro area of a bit more than 600,000. CyRide in Ames, Iowa, carries about 12,000 every day, and Missoula’s excellent Mountain Line moves about 4,500 a day.

I always have a lot of fun chatting with show-goers on the tram about where they come from and whether they use transit where they live. The typical answer is that they don’t, and sometimes they even say they don’t think their tax dollars should have to subsidize transit at all. When I point out that the tram just saved them a 40-minute walk from their campsite to the Red Barn store, and that a portion of their admission fee was used to provide the trams, they begin to see the connection. You can practically see the light bulb pop on above their heads.

So this isn’t just an aviation story. It’s a transit story. And it should matter to mayors, city councils, and state legislators just as much as it matters to airshow planners.

We’ve seen this lesson play out in cities across the country. Kansas City made bus rides free and saw security incidents fall by nearly 40 percent while ridership and access to jobs improved. The fare-free Kansas City streetcar has produced a boom in retail along the route’s right of way. Olympia, Washington adopted a zero-fare policy and quickly rose into the top tier of U.S. metros for per-capita transit use. In Boston, a fare-free pilot doubled ridership on key bus lines and saved riders an average of $35 per month—while generating trips that wouldn’t otherwise have happened.

The takeaway is clear: free transit powers economic activity. When you eliminate the barrier of a farebox, you don’t just make it easier for people to get around—you enable them to spend more, participate more, and contribute more. Every AirVenture visitor who hops on a free tram is a customer delivered to a food stand, shop, or exhibit. Multiply that by 70,000 a day and you get $8.2 million in spending—a reminder that zero-fare transit is not a subsidy, but an investment in growth.

If Oshkosh can do it for a week every summer to move hundreds of thousands of visitors around an airfield, imagine what it could mean if more of our cities treated fare-free transit not as a subsidy, but as an investment in local economic growth.

"I wish to extend my appreciation to members of the Rail Passengers Association for their steadfast advocacy to protect not only the Southwest Chief, but all rail transportation which plays such an important role in our economy and local communities. I look forward to continuing this close partnership, both with America’s rail passengers and our bipartisan group of senators, to ensure a bright future for the Southwest Chief route."

Senator Jerry Moran (R-KS)

April 2, 2019, on receiving the Association's Golden Spike Award for his work to protect the Southwest Chief

Comments